Long before we ventured overseas, Byron and I had often discussed our shared desire to include train travel in our time abroad. Although the leading candidate at the time was India (we were still planning on going to Nepal at this point), the idea was quickly left on the table when our plans left us touring around Southeast Asia instead. While we were enjoying the light and fluffy in Japan though, Powder magazine published a story titled “The Great Siberian Traverse”; a full length feature that follows three prominent skiers as they trained across the vast expanse of Siberia, skiing wherever possible along the way. That was all the incentive we needed; if they could do it, why the heck couldn’t we? The plan was made and visas were secured; our route would take us by train from Beijing to Russia (via Mongolia), where our first stop would be the city of Irkutsk. With ten days in Beijing to kill before our train left for Russia, we had just enough time to explore one last corner of Asia before heading north into Siberia.

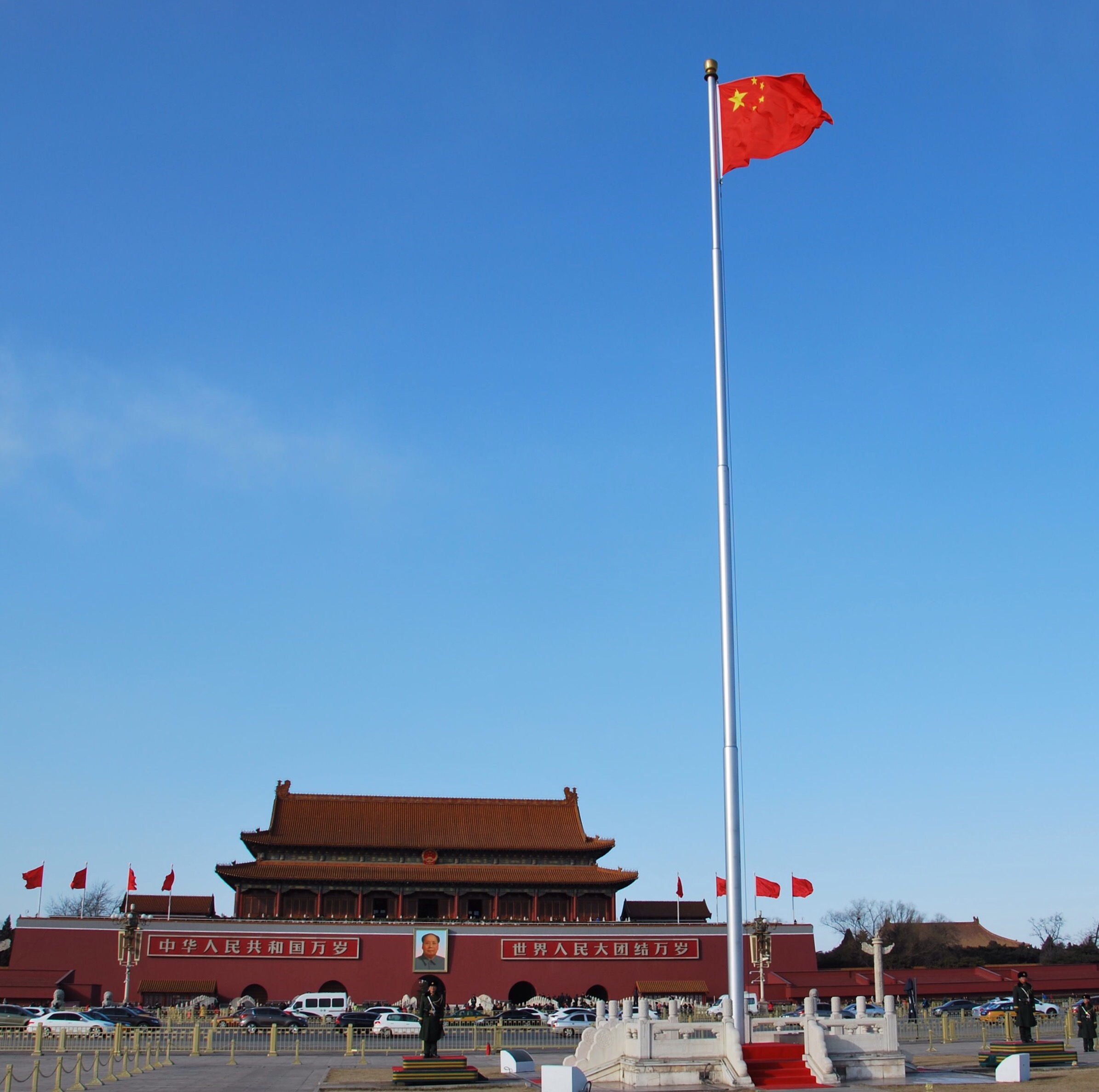

Our first day in Beijing was beautiful; the air was crisp and the skies were blue, while a chilly wind kept the skies clear of both cloud and Beijing’s infamous pollution. As the wind died off over the next day or two though and the smog began to settle back into the city, we quickly developed a desire to leave the city. By night cars illuminated the all-encompassing pollution which shone like fog in the headlights, and by day you could count those which had remained parked for the night as they became covered by a distinctive film by the next morning. If inanimate objects bore this coating of pollution on the outside after only a day, what on earth did the inside of our lungs look like after two?

Our escape came on the China Highspeed Railway. After a little research we set our sights on the Huangshan mountains, which sit 1300km south of Beijing, only a mere 6 hours away when transported by one of the country’s newest rail lines traveling at speeds of up to 300km/hr. Onboard the train the next day, we were afforded a unique (albeit quick) view of life in China’s rapidly expanding countryside. Much of it simply resembled one construction site after the other; although there were breaks in between where flocks of sheep and farmers still roamed through their rapidly shrinking pastures, everywhere we looked a new rail line, highway, or high rise was being built. The economic growth the country is experiencing thanks to its adoption of quasi-capitalist principles coupled with a commanding one party government has resulted in rapid expansion with little to no consultation; zipping through rural farming villages cut in half by a high speed rail, it was painfully obvious that this growth has come fast, and the rising tide hasn’t lifted all boats.

We arrived at our destination in time to catch the last bus of the day, and were delivered to our hotel in the small town of Tangkou under the cover of darkness. The next day we woke to clear skies (hooray!), surrounded by towering granite peaks. Excited to explore these peaks, we boarded the bus which would deliver us into the park and the start of the trails. Although still quite commercially developed (think paved stairs and garbage cans all the way up), it was wonderful to be outside experiencing another face of China. Quite similar to the landscape of California’s Yosemite National Park, Byron and I slowly made our way up the mountain where we would spend the night in one of the hotels perched on the side of the jagged peaks.

Due to cultural differences in dormitory and shared bathroom etiquette, what happened that night will unfortunately go down as the worst night in the history of our entire trip. Sleep deprived and disgusted, we threw on our clothes the next morning and set out to explore the remaining trails before making our way back down into the valley. The sun greeted us along with the weekend crowds as we descended the mountain, and I chuckled as Byron was stopped again and again for photos along the way with awe struck Chinese. I don’t know if it was his blue eyes, blonde hair or blue pants that won them over, but either way it was a photo op they weren’t going to miss. After a short tram ride down the mountain we were soon back on the bullet to Beijing, ready for the start of our next adventure. Skis and gear in tow we boarded the train a few days later, ready to see what Siberia had in store for us.

The true Trans-Siberian starts in Valadvostock On Russia’s far east coast, traversing 9000km across the word’s largest country to arrive in Moscow one week later. Rated as a more popular option however is the Trans-Mongolian route, which heads north through Mongolia from China before connecting with the Trans-Siberian rail line 50 hours later in Irkutsk, Russia. Once we had firmly wedged our skis and oversized bags into our sleeper berth we excitedly settled in to watch Beijing fade away. As we jostled and bumped through the countryside China soon faded away into the cold wilds of Inner Mongolia. We reached the border late that evening and took the stop as an opportunity to grab a breath of fresh air and stretch our legs. We laughed as a Malaysian couple whom we had made friends with earlier that day experienced their first breaths of cold air; newly married they had chosen the train trip to Russia’s capital for their honeymoon. We repeatedly assured them that even for seasoned Canadians, -20C is cold for anyone. Still sceptical they grabbed a few quick breathless photos and smartly retired to the warmth of the waiting train. The next day was spent comfortably traversing the Gobi desert, still deep in the grasp of winter. That evening we made one last midnight border crossing and sleepily smiled as the border official checked our visas and stamped our passports; we had just entered the Russian Federation.

Our first glimpse of Siberia was exciting; we awoke in the morning to beautiful sunshine and Lake Baikal on one side of the train, and spectacular snow capped mountains on the other. As we pulled into Irkutsk that afternoon and grabbed a taxi to our hostel, all we could think about were the chilly peaks we had passed by that morning and wondering just how the heck we were going to get back there to ski them.

Huangshan Mountains

Huangshan Mountains

Huangshan Mountains

Huangshan Mountains

Beijing metro on route to Siberia.

Gobi desert

Home on the rails

Home on the rails

Leg stretch. Ulaanbaatar, Monoglia